Glimpses of Healing and Hope

March 6, 2017

By: Jane Bishop Halteman

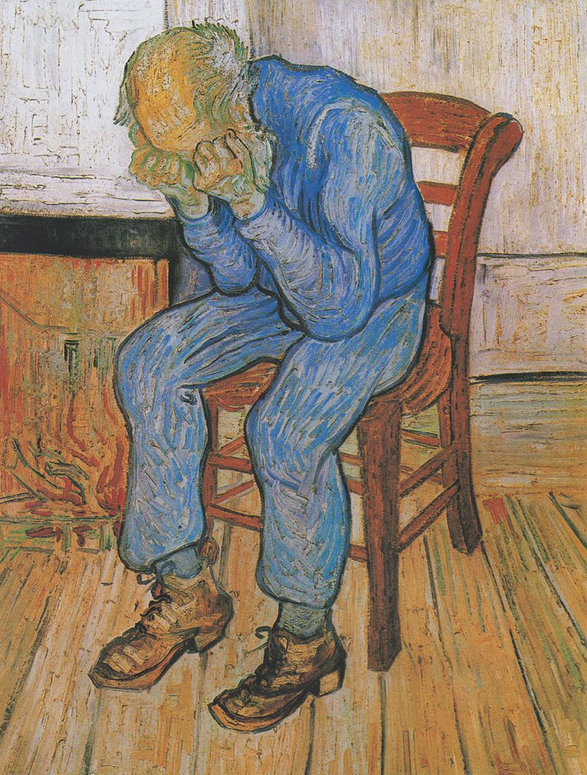

Vincent van Gogh's At Eternity's Gate, 1890, oil on canvas

“During Lent,” says Christine Valters Paintner in a Patheos piece published in 2011, “my practice will be truth-telling. I will inhabit my places of grief, the sorrows I have resisted up until now, and allow my unspoken lament to rise up in me like fire. I will turn off the endless noise and chatter that distract me from those places where my heart has hardened. I will be in solidarity with those who have no voice and listen for their silent groans. I will trust along with our spiritual ancestors who wrote and sang the Psalms in the assembly, that when I go to the rawest, most vulnerable places, my soul is then transformed....”

According to Valters Paintner, “Each one of us carries grief, sorrow that perhaps has gone unexpressed or been stifled or numbed. Each of us has been touched by pain and suffering at some time. Yet we live in a culture that tells us to move on, to get over it, or to shop or drink our way through sorrow.”

Listening to the fourth movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 in B minor Tuesday night at a Goshen College Performing Arts Series concert featuring the National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, I found myself lost in an intense crush of palatable pain and grief.

I knew little to nothing about this work and and its fourth movement prior to hearing it last week; when I googled it for more information, I was aware only that no music had ever moved me to such deep sadness in the way this piece did, so I was not surprised to discover that one listener called it “tragically and achingly beautiful.”

Perhaps the ability to recognize that beautiful but tragic ache requires that one has experienced some aspect of grief in life, as, of course, most of us have. In my case, I learned to manage, even stifle, a largely hidden sadness for many years, one brought on by the death of my boyfriend the summer after my sophomore year of high school and further compounded 12 years later by the death of my 18-year-old brother.

In the same way that the Tchaikovsky movement demands that we pay attention to our own griefs and losses, Vincent van Gogh’s At Eternity’s Gate allows us to surface private pain. Contrary to what we have sometimes been taught about van Gogh, Kathleen Powers Erickson writes in her book At Eternity’s Gate that “belief in a ‘life beyond the grave’ is central to one of van Gogh’s first accomplished lithographs, At Eternity’s Gate. Executed at The Hague in 1882, it depicts an old man seated by a fire, his head buried in his hands. Near the end of his life van Gogh recreated this image in oil (see above), while recuperating in the asylum at St. Rémy. Bent over with his fists clenched against a face hidden in utter frustration, the subject appears engulfed in grief. Certainly, the work would convey an image of total despair had it not been for the English title van Gogh gave it, At Eternity’s Gate. It demonstrates that even in his deepest moments of sorrow and pain, van Gogh clung to a faith in God and eternity, which he tried to express in his work.”

Erickson goes on to say that van Gogh’s Starry Night (see below), painted in 1889, “is a visionary masterpiece, recounting the story of van Gogh’s ultimate triumph over suffering, and exalting his desire for a mystical union with the Divine,” as suggested by “the cypress, which shoots up into the firmament like a giant flame.” The painting, she says, “reveals that he did not close the door on religious faith,” rather on organized religion as illustrated by the darkened church building. The work also depicts “the triumph of the mystic’s communion with God through nature.”

Valters Paintner suggests these practices to help create what she calls intentional space for grief: Make room for others to share their sorrows. Ask friends about their recent losses and listen well to their stories. Consider the ways you may unknowingly perpetuate the world’s pain. Speak your lament in public, perhaps via opinion pages. Write your own prayer of lament inspired by the Psalms. Practice truth-telling by refusing to say that all is well if it is not.

Whether our sorrow is personal or grows from the aches and pains so present in our own country and the world today, may we find ways to care for our private grief this Lenten season so that we might listen for the silent groans of those who have no voice.

Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas